by Fernando Medici, Mackenzie Presbyterian University

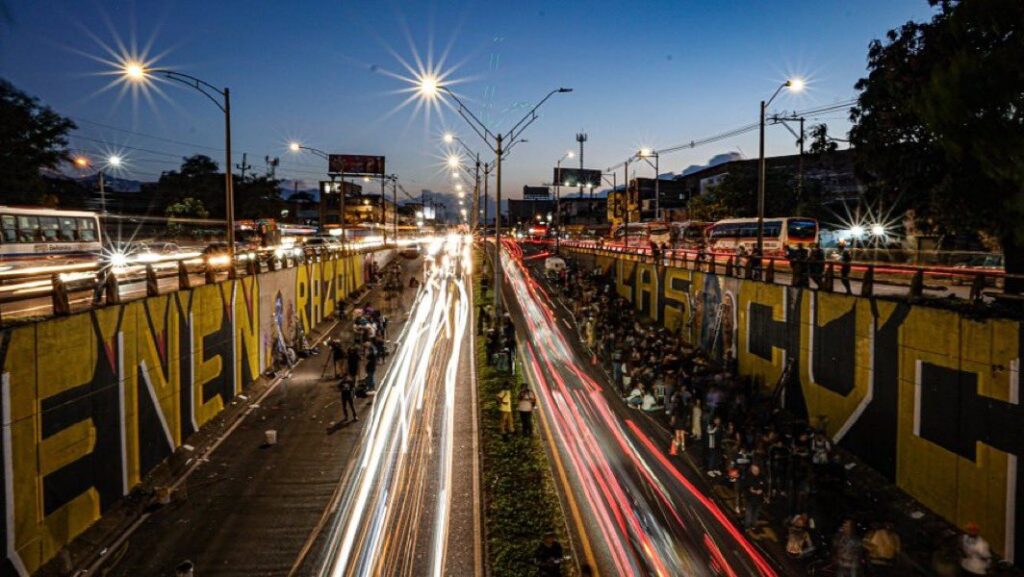

Photo Credit to Amauri Nehn/NurPhoto via AP

Few people outside of Brazil are likely aware that this South American country endured its own version of a Capitol attack. On January 8th, 2023 — two years after the infamous U.S. incident — a mob of supporters of former president Bolsonaro stormed government buildings, including Congress and the Supreme Court. This brazen assault on democratic institutions highlights the dangerous influence of right-wing radicalization and rampant social mediatized fake news, which continue to undermine the nation’s fragile democracy by amplifying a hate campaign against Brazil’s Supreme Court, and pleas for military intervention, while celebrating the insurrection that ended with Bolsonaro’s followers storming the Supreme Court Building.

Like its American counterpart, the unrest was fueled by unsubstantiated claims of election fraud following Bolsonaro’s defeat at the polls. However, what set Brazil’s crisis apart was the additional troubling involvement and support of several high-profile military figures.

Subsequently many of the insurgents were indicted, but until recently little had been done regarding the still unknown leadership of the movement.

That changed this past November as former President Jair Bolsonaro and 36 others were indicted by Brazil’s Federal Police for crimes including an attempted coup d’état, violent abolition of the democratic rule of law, and involvement in an alleged attempt on the lives of President Lula, Vice-President Geraldo Alckmin, and Supreme Court Minister Alexandre de Moraes.

Of course, despite the political weight of these charges, an indictment is not equivalent to a conviction and does not automatically lead to a trial. It only provides evidence for the Prosecutor General’s Office to decide whether to proceed with the case or not. This is not the first time Bolsonaro has been indicted. He was previously implicated in investigations for fraudulent vaccine records and for trying to conceal Saudi Jewelry he was gifted as president, which, according to Brazilian Law, belongs to the government. Both criminal proceedings are currently underway, and Bolsonaro is prohibited from leaving the country.

Regarding the coup d’état-related indictments, after an extensive investigation, the Brazilian Federal Police concluded that the alleged coup attempt was supposed take place in late 2022, after Bolsonaro’s election defeat and led by prominent military figures, including General and formal State-Secretary Mario Fernandes and General Braga Netto, Bolsonaro’s vice president candidate in the most recent election. According to the investigators, Bolsonaro was aware of and supported the coup efforts.

This case underscores the frail state of Brazilian Democracy after years of political radicalization and the unchecked spread of rampant fake news. In large part the proliferation of fake news has been fueled by Bolsonaro’s “Hate Cabinet”, a group led Bolsonaro’s sons Flávio and Eduardo and responsible for managing far-right social networks, the spread of misinformation, and promotion of hate campaigns against Bolsonaro’s political adversaries.

Now, Brazilians await conclusion of the legal process. Expectations are that at the soonest a possible legal action could be filed next year, since the General Prosecutor’s Office will need months to go through the evidence.

Uncertainty surrounding the legal process and the timeline for potential action reflect the broader challenges facing Brazilian institutions and democracy. While the indictments represent a significant step toward accountability, the slow pace of the justice system underscores deeper institutional challenges, exacerbating political polarization and social mistrust. It also feeds narratives of persecution and bias, particularly among Bolsonaro’s far-right supporters, who often portray the judiciary as politically motivated. The credibility of the Brazilian Supreme Court, already eroded by its controversial role in the Lava Jato operation and its perceived partisanship during past political crises, now faces renewed scrutiny. In a country already deeply divided along ideological lines, its lack of perceived impartiality risks intensifying public skepticism, further destabilizing Brazil’s fragile democratic institutions.

It is not a surprise that Bolsonaro supporters have dismissed the allegations against him as political persecution and remain entrenched in their views, further deepening political rifts in Brazilian society. When large segments of the population operate under different understandings of reality, it becomes nearly impossible to foster the trust needed for a healthy democracy.

This scenario places Brazil’s democratic institutions under considerable strain. The 2023 storming of Congress and the Supreme Court demonstrated the vulnerability of these institutions when confronted with coordinated antidemocratic efforts. Now, with claims of military involvement, the alleged coup raises serious questions about how long Brazilian democracy can continue to withstand such blows.

The problem is made worse by Bolsonaro’s hate campaign against the Supreme Court, which has eroded trust in the institution, guaranteeing that any legal decision against him will be seen by a large subset of Brazilians as corrupt and politically motivated.

If Brazilian democracy is to survive, it will require more than just the prosecution of a few individuals, even if they are high-profile. A broader effort to rebuild trust in democratic institutions and to reduce the spread of misinformation will also be necessary. Without addressing the root causes of radicalization and polarization, Brazilian Democracy will continue to be vulnerable, whether to attacks by Bolsonaro’s followers or other political groups.

This piece can be reproduced completely or partially with proper attribution to its author.